Tuesday evening’s educational event, hosted by George Mason University (GMU) and the Institute of Biohealth Innovation entitled “Keeping our soldiers safe: Understanding, Preventing and Treating TBI,” was a huge success. We had multiple sponsorship tables set up throughout the auditorium so that those in attendance could gather information about what services are offered to our servicemembers and veterans. A special thank you to NovaVets, MTEC (Medical Technology Enterprise Consortium), Coming Home Well, GMU Center for Psychological Services, Department of Veterans Services, Center for Neurosciences and Regenerative Medicine, Hope for Warriors, and Concussion Legacy Foundation/ Project Enlist for their sponsorship and collaboration for such an important discussion on TBI.

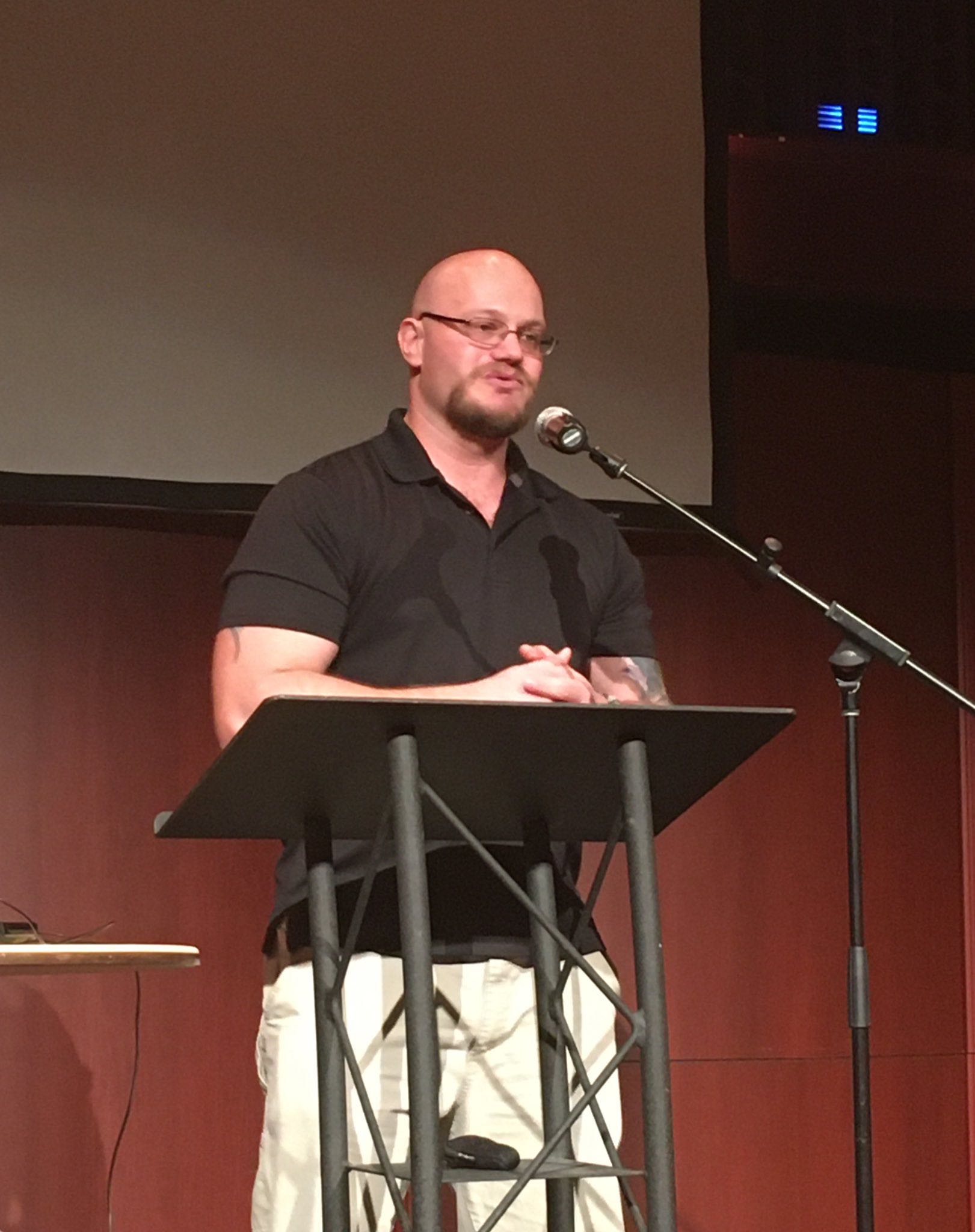

The event began with opening introductions from Professor & Chair of GMU Department of Psychology Keith D Renshaw, PhD and GMU Psychological Services Clinical Professor Robyn Mehlenbeck, PhD. Our first speaker was former Army Sgt. Thomas Bates, who spoke about living with the health struggles of multiple blast related TBIs. He emphasized the importance of veterans and their families working alongside the scientific community to push brain research further in order to understand the lasting effects from trauma. He articulated the “WHY” question that many vets ask themselves. “Why am I this way? Why am I feeling this way? What can I do to fix it?” He discussed the importance of a collaborative effort within the community in the overall treatment for veterans as they reintegrate into civilian society.

The event began with opening introductions from Professor & Chair of GMU Department of Psychology Keith D Renshaw, PhD and GMU Psychological Services Clinical Professor Robyn Mehlenbeck, PhD. Our first speaker was former Army Sgt. Thomas Bates, who spoke about living with the health struggles of multiple blast related TBIs. He emphasized the importance of veterans and their families working alongside the scientific community to push brain research further in order to understand the lasting effects from trauma. He articulated the “WHY” question that many vets ask themselves. “Why am I this way? Why am I feeling this way? What can I do to fix it?” He discussed the importance of a collaborative effort within the community in the overall treatment for veterans as they reintegrate into civilian society.

Dr. Dara Dickstein, an associate professor and brain researcher from Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, spoke about current research by the Department of Defense and Boston University. She discussed the background of TBI, sub concussive effects, CTE, and astroglial scarring within our military population.

Dr. Dickstein discussed shearing of the grey and white matter of the brain during blast exposures. She reported that while CTE cannot be diagnosed in a living person to date, there numerous clinical trials currently being conducted. She stated the lasting effects in chronic TBI cases can manifest as changes in mood, cognition, memory loss, behavior, impulsivity, anxiety and apathy. However, these symptoms are similar to other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s Disease, Hicks Disease, Frontal Temporal Dementia, and any other tauopathy disease. Even with recent advances in medicine the brain remains an unknown front waiting to be explored.

Dr. Dickstein continued her discussion of case studies of CTE found in postmortem brains of veterans. She referenced Dr. Dan Perl’s research on astroglial scarring in veterans, even when there was no CTE tauopathy present. This research is still in process and opinions about what occurs in the brain after blasts in the scientific community, but there has been a collaborative effort to research it.

So what methods can be used to explore the brain and diagnose CTE in a living person? As mentioned above, clinical trials are using biomarkers to look for CTE in addition to MRI, advanced PET imagining, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and saliva testing. The military population is more challenging and complicated because we’re dealing with deciding what might be TBI versus PTSD versus CTE. The symptoms are all similar and thus they can be misconstrued for one another.

Dr. Dickstein discussed using neuroimaging of a specific radioactive tracer has been effective in identifying “hot spots” of tau tangles in some pre-clinical trials, but more research needs to occur to validate this method. There are many variations between the subjects because of differing life experiences such as: number of blast exposures, number of sub concussive events, other head injuries from sports, preexisting conditions, a loss of consciousness, no loss of consciousness, natural aging processes, etc. What is important to know is we don’t know the prevalence of CTE in the general population or the military population due to varying factors and selection bias. Scientists researching CTE came to the revelation that we need to reevaluate how we’re diagnosing CTE because there is currently several different methods and practices being utilized. By coming to a consensus everyone will use the same processes which will allow for better accuracy and reliability in diagnoses.

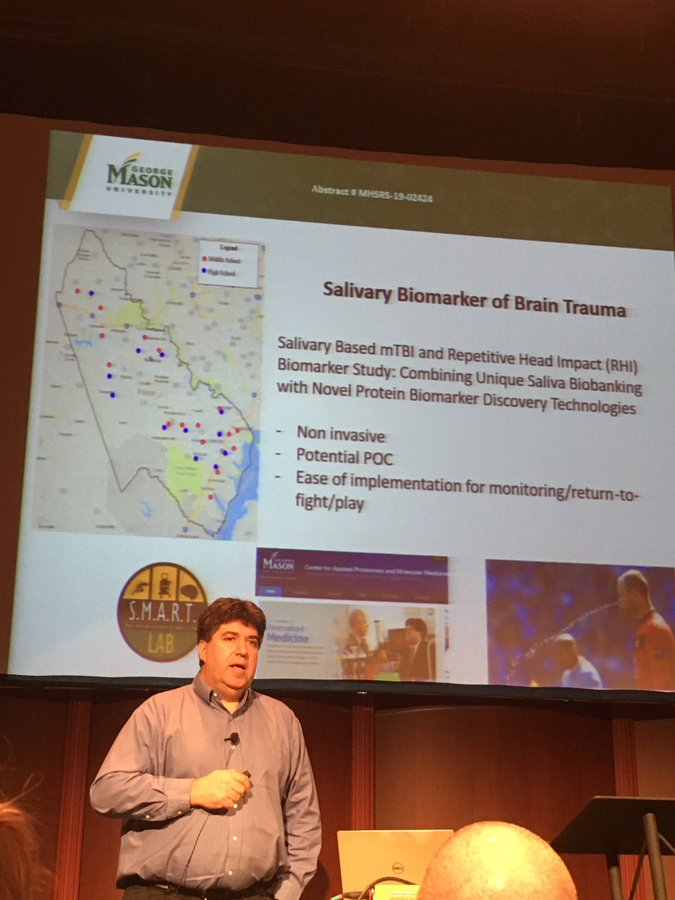

Our next guest was Dr. Emanuel Petricoin who is co-director of the Center for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine at George Mason University. He discussed the research on potentially utilizing saliva biomarkers to diagnose youth concussion and TBI both on the battlefield and field of play. The hope is to be able to not only identify early stage concussions and TBIs but also determine when it is safe to return to play. Dr. Petricoin noted using such biomarkers may not be well received for fear of not returning to duty or play.

Our next guest was Dr. Emanuel Petricoin who is co-director of the Center for Applied Proteomics and Molecular Medicine at George Mason University. He discussed the research on potentially utilizing saliva biomarkers to diagnose youth concussion and TBI both on the battlefield and field of play. The hope is to be able to not only identify early stage concussions and TBIs but also determine when it is safe to return to play. Dr. Petricoin noted using such biomarkers may not be well received for fear of not returning to duty or play.

Dr. Petricoin went into further discussion on the statistics that females have a higher concussion rate and severity than males due to their neck musculature being not as developed and differences in skull thickness. In conjunction with his colleague Shane Caswell, both doctors are following youth athletic programs, with parental consent, by collecting and testing saliva. The children will be followed from preseason to off season in counties throughout the state of Virginia. Around 500,000 youth are treated in hospital ERs for TBIs a year. It has been discovered there is no gender specific helmets made for sports or military personnel to make up for the contrasting differences in the two.

Altogether, the evening was very informative and many in attendance asked questions and were genuinely concerned with understanding all that was discussed.

Libby